Japonism, from the French word “Japonisme” is the name given to the passion for Japan in decorative arts at the end of the 19th century. This term is used for the first time in 1872 by the art critic Philippe Burty (1830-1890). In hindsight, it’s possible to temporally limit this movement from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century.

The enthusiasm for Japan can be explained thanks to surprise effect and scarcity: indeed, this country was closed for a long time to international trade. Japan’s opening to the world at the end of the 19th century generated great interest, supported by some merchants and collectors who widely participated to its diffusion, more and more significant in decorative arts and furniture, leading at the same time a long-term tendency effect for many years. The passion for this country was so strong that it was a true catalyst in all arts in general.

The year 2018, which just finished, was the year of the celebration of the 150th anniversary of the Peace, friendship, and trade treaty between France and Japan and allow us the occasion to revisit the start of an idyll between Japan and France at the 19th century.

Japan, history of an isolated peninsula

The Japonism in Art can only be fully conceived by taking the measure of the geopolitical history of Japan and its relations with other nations, with Occident in particular. The first contact between Occident and the archipelago was done on the initiative of Portuguese, from 1543. Their presence was followed by other Europeans, notably Jesuit missionaries as Saint François-Xavier which established and entrenched a fruitful trade on behalf of Portugal.

If strangers were first tolerated, rapidly Japanese took the habit to call strangers “Naban”, literally “South barbarians”, a strong term that traduce the decrease esteem of Japanese for strangers. The first times of cohabitation were slightly peaceful and the trade, as the cultural exchanges between Japan and Occident, were dense. At this period, an Indo-Portuguese art appeared, also sometimes called or connected to Naban art, born from the mixing of these different influences.

However, the growing Christianity ended to worrying Japanese populations, who could not tolerate any longer the presence of these barbarians appearing unworthy of their culture, traditions and very few sophisticated! Christianity was forbidden from 1613 and violent repressions struck on Christians from the beginning of the 18th century. Japan gradually closed its doors to Europeans 1 and in 1650, the Christians as the almost all strangers remaining in Japan were liable to the death penalty, like the Japanese who wanted to leave the archipelago!

Indeed, for about two centuries, Japan was, with some exceptions with Holland and China, isolated. It was the Americans who tried first to break this autarky, by strength, in 1853. The undertaking, initiated by the Commodore Matthew Perry, finally ended to the Kanagawa Convention in 1854, which authorized the refueling of American ships in two Japanese ports. Right after, trade treaties named Ansei, were signed between Japan and other countries such as the United States, and then four other European countries, including France with the signature, the 9th October 1858, of the Treaty of Amity and Commerce between France and Japan. Thereafter, in 1868, the Shogun regime and feudalism were overthrown. The Japan Emperor Mutsu Hiro (1852-1912) relocated the capital city to Edo, renamed Tokyo, and decided that its country will become “a modern nation by taking model on Occidental world” 2. Japan was ready to go to the Occident conquest!

The opening of the Japanese culture to Occident

If a small Japanese delegation, essentially Shogunate, went to the Universal Exhibition of London in 1862, they were here in a mainly passive way because she didn’t take an active part to the exhibitions. Indeed, Japanese items exhibited belonged to the first general consul of Great Britain in Japan, Sir Rutherford Alcock 3.

It was truly the Universal Exhibition of Paris in 1867 that marked for Japan the first participation to an international major event. Several pavilions were constructed on the Champs-de-Mars and notably one, where geishas reproduced the famous tea ceremony for visitors. Many Japanese exponents won honour, gold or silver medals and art critics didn’t stop to laud this new nation that they considered superior to China, which had them made so much dream for a time!

The Parisian edition of 1878 confirmed the Japanese great success already met in 1867: sabres, firearms, tea, spices, fans, engravings, small items and furniture in the Japan fashion were omnipresent! The success didn’t decrease throughout Parisian editions in 1889 and in 1900. A fascination for Japan truly felt into place and the important measure occupied by Japan in Universal Exhibitions was a true indicator. Indeed, these events were “both a taste mirror and an industrial stimulating, they were essential to trade development” 4 and were full part actors in the construction of this tendency.

Another factor intervened in the diffusion of Japanese art: the role of collectors and sponsors. Among them, the inescapable merchant and collector Siegfried Bing (1838-1905), trader in Paris, who quickly realized his first trip to Japan in the 1880’s and opened three new sale points in Paris in addition of its initial shop at the 19 rue Chauchat: Fantaisies japonaises (Japanese Fantasies); he also established directly in Japan in 1887 to Yokohama and Kobe. His role was major because he lent many objects during Universal Exhibitions and committed to developing the pedagogy around Japanese culture and technical know-how. Notably permitted to students of the French Arts and Professions Conservatory to access to his artwork. He created a magazine, Le Japon artistique (Artistic Japan), and participated to valuations and to the creation of specialized publications. He was one of the major actors during the increase of Japonism at the end of the 19th century, one of the catalysts of this new passion and, paradoxically, one of the first to feel the wind turned for Art Nouveau 5.

Another major merchant, Japanese origin, Hayashi Tadamasa 6, also played a major role in sale and deepening of the Japan knowledge. And without necessarily being merchants, many personalities of this period, art critics or even artists, were confirmed Japonists as Philippe Burty, Emile Guimet, Isaac de Camondo, Goncourt brothers, Joris-Karl Huysmans, Guy de Maupassant, Louis Gonse or James Mc Neil Whistler and James Tissot 7!

Interpenetration of Japonism into Art

Among Japonism collectors, we found many artists and craftsman. Very visible into exhibition and collections, Japonism ended necessarily to be integrated and mixed to the occidental art. Concretely, the area where this integration was the most noticeable is into graphic arts, thanks particularly to the Japanese prints with the influence of the two masters in this field: Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) and Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849).

By proposing a new poetical vision of landscapes, a new treatment of the perspective and the spatial organization, a different reflection about shape and colors complementarity, Japanese prints intruded on painting 8, releasing it from his realistic stranglehold.

Japanese prints but also Japanese architecture, Japanese culture and all its decorative vocabulary were major influences bringing a strong and noticeable renewal in decorative arts, ceramic and object production. To give an example, the first manifestation of the japonism into decorative arts was the porcelain table service ordered by Eugène Rousseau to Félix Bracquemond in 1866 9, showing the first overview with a clearly occidental shape, based on Louis XV style, and a decoration inspired by Japanese album for Hokusai and Hiroshige, recently discovered in France. The blue combs on edges framed Japanese inspired animals and plants, with an organization close to the oriental pastiche that allowed access, in a way, a pattern and a framing still hard to picture for a non-specialized public 10.

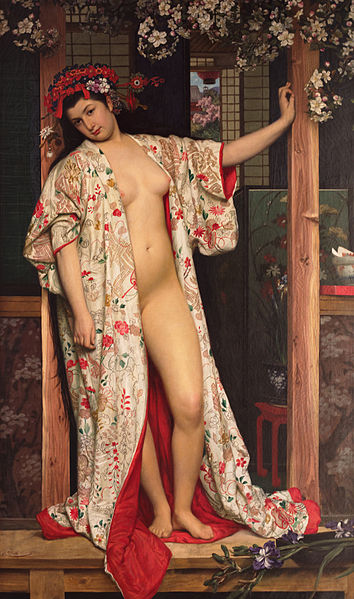

1.James Tissot, La japonaise au bain, 1864

2.Claude Monnet, La japonaise, 1876

3.René Lalique, Peigne aux ombelles, vers 1897-1898, ©Photo Les Arts Décoratifs, Paris/Jean Tholance

4.Baccarat, Vase en cristal gravé, vers 1870, ©Photo Les Arts Décoratifs, Paris/Jean Tholance

5.Barluet et cie, Creil, Vase au martin-pêcheur, vers XIXème siècle ©Photo Les Arts Décoratifs, Paris/Jean Tholance

6.Félix Bracquemond, Creil, Lebeuf Millet et Cie, Service Rousseau, Assiette plate, 1866 ©Photo Les Arts Décoratifs, Paris/Jean Tholance.

7.Emile Gallé,Vase soufflé à la libellule et papillons, 1887 ©Photo Les Arts Décoratifs, Paris/Jean Tholance.

Japonism in furniture

Painting and a wide range of the decorative arts underwent a deep transformation because of the discovering of the Japanese art; if we considering furniture as a slightly different entity from decorative art, we have to precise right away that furniture has been not left behind from this new trend.

A first difficulty appears in the specific furniture area: when we are thinking to Japan in here, we are commonly considering the lacquer work. Indeed, like the Chinese, Japanese skilled the lacquer art for a while. If Japan quickly closed its doors and remained difficult to access, some skilled craftsmen like the French Bernard II Van Riesen Burgh (1700-1760), more known as B.V.R.B., already used Japanese lacquer panels from time to time. Those panels came from exported furniture before the Japan closing, or from the many few authorized people to deal with Japanese during the isolationist period, like Dutch. The marchand-merciers 11, and more particularly Hebert, became specialized in the furniture cutting up to isolate lacquer panels and sold them separately to create new furniture with them; we know that Lazare-Duvaux one of the main marchand-mercier of Mrs. de Pompadour, practiced that too. This is how we can find, on the middle part of the B.V.R.B.’s commode for the French Queen Marie Lezcinska (1703-1768), delivered in 1737 for the retreat cabinet of the Fontainebleau castle (n°OA11193) a Japanese lacquer panel framed by chiseled and gilt bronzes and achieved by French Vernis Martin 12 to make a perfect illusion of a full real Japanese lacquer furniture.

This first importation of know-how remained tiny and kept European accents: general shape of furniture frames was still very occidental. Indeed, following the example of this BVRB’s commode, the scalloped shape with two drawers sans traverse, slightly bulged façade and flared sides to the back was a shape already used by Charles Cressent[1] who very loved wood marquetry, so entirely unrelated with the lacquer.

Finally, and maybe above all, during the 18th century, the word “chinoiserie” gathered all that could possibly come from China… but also from Japan, or just inspired by 14. So at this time, everything still had to be done.

If a part of the Japanese production, as the lacquer, therefore, was already known in France before the emerging of Japonism, an ideological change happened in the 19th century: Japan was not foreseen like a Chinese culture and 18th century’s chinoiseries annexation anymore but as an independent ensemble. Japonism appeared in a right time into the history of the furniture creation since it brings a real innovative impulse on an eclectic production of the late 19th that never stopped to turn itself on re-visiting past styles. But even if new ideas and shapes emerged with those blends and reinterpretations, the Japonism offers a more ultimate solution. Its impact is plural: he transcended shapes, revolutionized material and expressed itself on many objects.

Terms and impact of the Japonism rising are perfectly summarized in Jacqueline du Pasquier word reproduced hereafter:

“Indeed, at the opposite of chinoiserie that was “ a pure emanation of the occidental tradition” (cf. Alain Gruber, The decorative art in Europe, Classic and Baroque, p.227) inherited from a more or less phantasmagoria Orient, Japonism has, at the beginning, a more concrete and immediate approach, more than it could be in the 18th century for a country, until then and for more than two centuries, entirely self-contained and so almost entirely unknown and mysterious. The discovery’s choc is just more important. Another particularity of this new relations East-West is that, from the outset, the Japanese were determinate to not being treated as an Occidental colony, such as it was the case for China.” 15

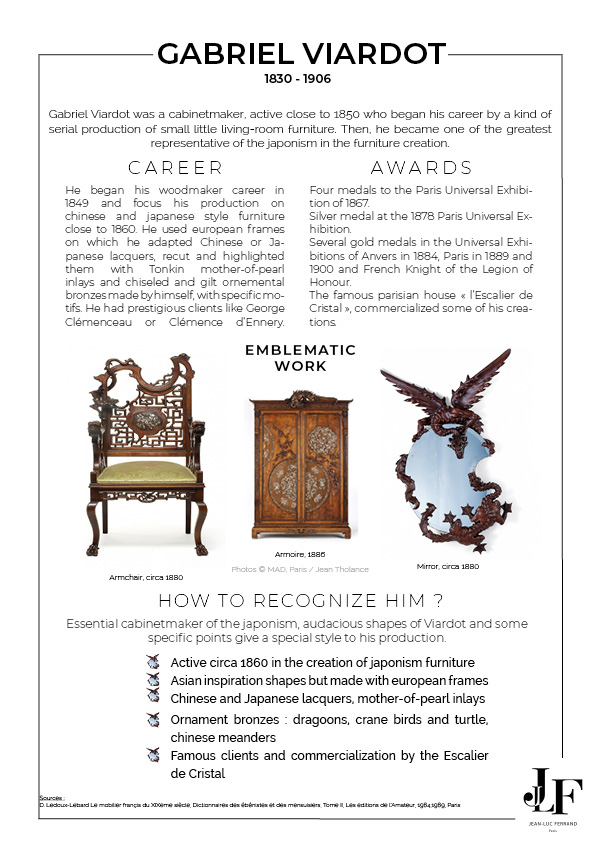

If the terms of Japonism are new, consequences on the furniture production reminded kind of previous passion for chinoiseries and turqueries in the 18th century. Worthy collectors and lovers should be able to furnish an entire room in the Japanese style to travel and make travel his guests. Cabinetmakers and Manufactures such as Gabriel Viardot, Duvinage and Giroux, Edouard Lièvre, La Maison des Bambous of Perret and Vibert etc, will specialize themselves in this new gender furniture, which became very successful. That’s why they quickly produced important quantity, strongly helped with industrialization progresses, in such a way that a wide range of the bourgeoisie could furnish itself in the Japanese style. It explains also that the production was extremely diversified in all those different workshops from this late 19th century.

Some examples of furniture creators :

A sheet about the French cabinetmaker Gabriel Viardot. To upload it, click here or on the picture.

Mais aussi…

Presented objects :

1. Christofle & Cie, Vase-Torchère, Email cloisonné et bronze doré, 1874, MAD ©Paris, MAD / Jean Tholance

2. Edouard Lièvre (aut.), Ferdinand Barbedienne (bronzier), Masayoshi (bronzier), Jardinière, bronze, vers 1870 MAD ©Paris, MAD / Jean Tholance

3. Veuve Ferdinand Duvinage, ancien magasin Alphonse Giroux à Paris, Cabinet en palisandre, marqueterie d’ivoire et bois divers à cloison métalliques et bronze coloré (“mosaïque combinée”), vers 1878, Paris, Musée d’Orsay

4. Emile Gallé, Etagère en noyer mouluré et sculpté, marqueterie de bois divers et bronze patiné, 1894, Nancy, Musée de l’école de Nancy

5. Edouard Lièvre, Edouard Detaille (peinture), Meuble à deux corps en palissandre de Rio, ébène des Indes, bronze doré et fer gravé incluant une peinture, 1877, Paris, Musée d’Orsay

As we said, Japonism offered a quasi-providential solution in a crisis period for decorative arts but was also a kind of end state. With it, it’s the end of a period and it allows a transition to new attractive spots and plastic, formal and artistic researches that animate the beginning of the 20th century.

It was clear that the Japanese decorative repertoire as the discovery of new shapes, materials, colors had a first plan role in the elaboration of Art Nouveau but also sometimes, in a less obvious way, in all artistic researches of different art currents and sectors. The echo of this movement lasted during many years in a noticeable way, in particular in the creations of the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) or in the 1920s with the ceramic of the English Bernard Leach (1887-1979), known to have made a bridge between Orient and Occident.

Yet today, many artists and craftsmen are concerned and soaked, in a protean way, by one or many aspects of the Japanese art. With his canvas with animal and foliage motifs, with a gilt background, the French contemporary artist Thibault, offers to us very personal and decorative artworks which remain a perspective and linearity inspired by Japanese drawings and shimmering colors of byobû (Japanese screen) with a gilt background from the Edo period.

Japonism at JLF Antiquités

NOTES

↑1 Indeed, the powerful Shogun regime of the Tokugawa dynasty leaded to a strong isolationist policy

↑2DU PASQUIER J., « Japonisme », in GRUBERT A. L’art décoratif en Europe, du Néoclassicisme à l’Art Déco, Citadelles & Mazenot, 1994, Paris, p .204

↑3Ibid, few hundred of porcelains, bronzes and prints of its personal collection.

↑4Ibid. p.205

↑5In 1895, he recalled its shops « L’Art Nouveau ». True tendencies’ visionary, Bing always stayed open-minded, notably by exhibiting different artists such as the Nabis, Claudel, Signac, Munch in parallel of his passion for Japonism. This adaptability allowed him to be attentive to the true artistic renewal emerging from this pivotal period and to succeed in the transition with Art Nouveau.

↑6Hayashi Tadamasa(1853-1906), born Nagashi Shigeki, was one of the most important Japanese art merchant in Paris during the second part of the 19th century. Associated to Wakai Kanesaburo, they opened their shop Wakai Hayashi to the 7 rue d’Hauteville and then moved to the 65 rue de la Victoire, near to Siegfried Bing that they directly compete with. He played a major role in the increase of the popularity of Japan and the deepening of knowledge that were relative to him throughout his exhibitions curating, his translations, the conferences he animated and his expert role.

↑7Siegfried Bing has been nominated as an expert for the inheritance sales for the Japanese items of Philippe Burty and Edmond de Goncourt after their death. The circle is complete between Japanese art amateurs, and unfortunately, the place misses us to quote all them.

↑8Claude Monet collected Japanese prints and dressed his wife in a kimono to paint La japonaise in 1876. Van Gogh was also a great collector and he said to his brother Theo in a letter dated from July 15th, 1888 « All my work is a kind of based on the Japonaiseries … » he painted bridges endlessly, like Hokusai. Mary Cassatt’s work also had such influences.

↑9The table service was first shown at the Universal Exhibition of Paris in 1867 and on following editions. It was re-made more than 80 times and only the degradation of the engraving stopped its production. Cf DU PASQUIER J., op.cit., p.255 ;

↑10Ibid.

↑11A “marchand-mercier” is a French term for a type of entrepreneur working outside the guild system of craftsmen but carefully constrained by the regulations of a “corporation” under rules codified in 1613. The reduplicative term literally means a merchant of merchandise, but in the 18th century took the connotation of a merchant of “objets d’art”. Earliest references to this “Corps de la Ville de Paris” can be found at the close of the 16th century, but in the 18th-century marchands-merciers were shopkeepers but they also played an important role in the decoration of Paris homes.

↑12Varnish named after its creator

↑13BARBIER M. Notice de la Commode Inv : OA11193 on the Musée du Louvre websiteURL = https://www.louvre.fr/oeuvre-notices/commode-3 consulté le 7/02/2019

↑14About that see DU PASQUIER J., op. cit., p.197

↑15Ibid. p.204

SOURCES (FRENCH )

ALCOUFFE D., DION-TENENBAUM A., LEFEBURE A., Le Mobilier du Musée du Louvre, Paris, 1993, t. 1, pp. 140 – 143.

DUCHESNE DE BELLECOURT G., « L’exposition Chinoise et Japonaise », Revue des deux mondes, 1er août 1967, Paris, pp.722-742

Exposition universelle de 1867 à Paris, Catalogue Officiel Des Exposants Récompensés Par Le Jury International, Dentu, 2e édition, revue et corrigée, Paris, 1867., p.12

DU PASQUIER J., « Japonisme », in GRUBERT A. L’art décoratif en Europe, du Néoclassicisme à l’Art Déco, Citadelles & Mazenot, 1994, Paris, pp.197-287

LEDOUX-LEBARD D., Le mobilier français du XIXeme siècle, Dictionnaires des ébénistes et des mensuisiers, Tome I & II, Les editions de l’Amateur, 1984,1989, Paris

MONTANI P., « Exposition Universelle – Les habitations japonaises », Le Monde Illustré, 28 Septembre 1867, p.198

Webographie

BARBIER M. Notice de la Commode Inv : OA11193 sur le site du Musée du Louvre URL = https://www.louvre.fr/oeuvre-notices/commode-3 consulté le 7/02/2019

BARBIER M. Notice de la Commode Inv : OA11292 sur le site du Musée du Louvre URL = https://www.louvre.fr/oeuvre-notices/commode-6 consulté le 7/02/2019

Site du Musée des Arts Décoratifs, URL = https://madparis.fr/ consulté le 7/02/2019

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, ressources sur Gallica et notamment les dossiers sur les expositions universelles URL = https://gallica.bnf.fr/html/und/asie/aux-expositions-universelles# consulté le 7/02/2019

Site du Musée de l’Ecole Nancy , URL = http://www.ecole-de-nancy.com/web/index.php?page=presentation-men, consulté le 7/02/2019